The Science of De-Extinction Is Closer Than You Think

Bringing back extinct animals might sound like something straight out of Jurassic Park, but scientists are actually working on it right now. Thanks to advances in genetic engineering, cloning, and DNA recovery, the idea of de-extinction is moving from pure fantasy into the realm of real scientific research. It is not just about movies and novels anymore. Laboratories around the world are studying how to piece together lost genetic blueprints to recreate animals that disappeared decades, centuries, or even millennia ago.

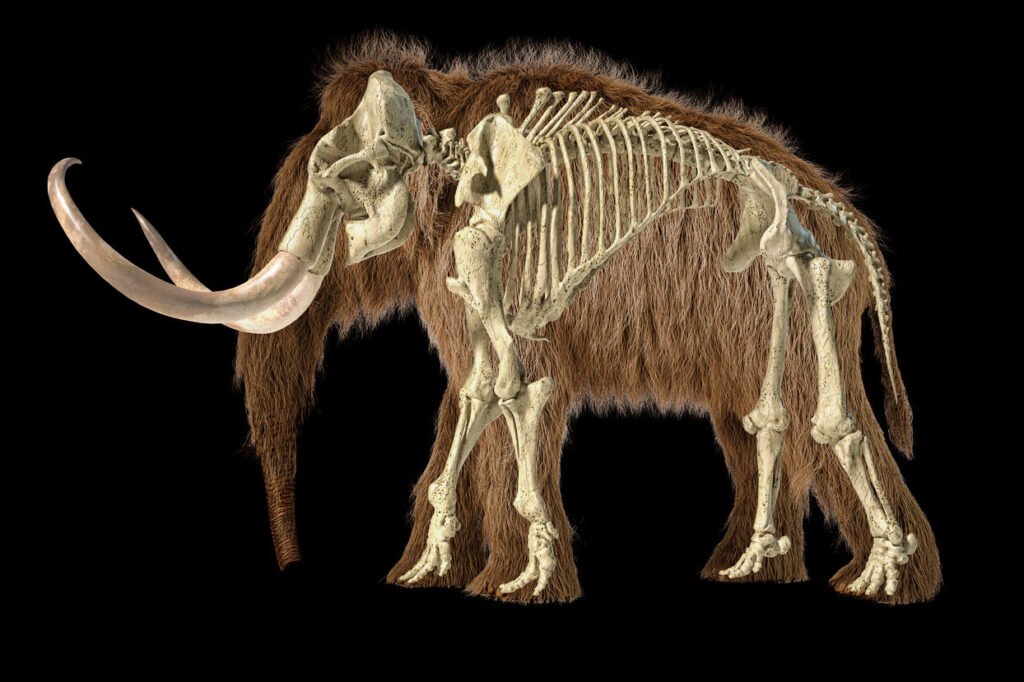

Experts in genetics explain that de-extinction mostly depends on finding preserved DNA. Some species, like the woolly mammoth and the passenger pigeon, have left behind enough genetic material that researchers are attempting to recreate their cells and, eventually, living individuals. The process is complicated, controversial, and full of technical hurdles, but it is no longer dismissed as impossible. Humanity may be standing at the beginning of a new era, where extinct creatures might once again roam the Earth or at least a controlled wildlife reserve.

DNA: The Ultimate Puzzle Piece for Extinct Animals

Reviving extinct animals is like trying to complete a giant, ancient jigsaw puzzle only many pieces are missing, and some have been warped by time. DNA is at the heart of the effort, acting as the instruction manual for life. But pulling usable DNA from long-dead species is incredibly challenging. Time, temperature, and the environment can all degrade DNA until it becomes a fragmented mess.

Scientists working on de-extinction projects often have to reconstruct DNA from surviving bits and pieces, filling in gaps with the help of closely related species. For example, Asian elephants are being used to help fill missing genetic codes for woolly mammoths. It is not about cloning a perfect replica, but about creating a living, breathing approximation. This careful genetic engineering raises deep questions about authenticity and the fine line between resurrecting an animal and building a hybrid inspired by it.

Cloning Could Be the Key But It Is Not Perfect

Cloning sounds like the straightforward path to bringing back extinct animals, but it is filled with complications. The technique involves taking the DNA from an extinct animal and inserting it into the egg of a closely related living species. That egg is then implanted into a surrogate mother to develop. This is how Dolly the sheep, the world’s first cloned mammal, was created back in the 1990s.

However, cloning extinct species adds an extra layer of difficulty. In many cases, the DNA is incomplete or damaged. Also, finding suitable surrogate mothers for long-extinct species is no small task. Scientists also warn that cloned animals can suffer from health problems, lower survival rates, and ethical concerns. Cloning could be part of the answer, but it is unlikely to be the silver bullet. Instead, it is one tool among many that researchers hope to refine to bring extinct creatures back to life or something very close to it.

Some Animals Are Better Candidates Than Others

Not all extinct animals are equal when it comes to the possibility of bringing them back. Some species left behind well-preserved DNA, making them realistic candidates for de-extinction. Others, like dinosaurs, are almost certainly beyond our reach because their DNA has degraded completely over millions of years. So even though Jurassic Park is thrilling to watch, resurrecting a real velociraptor is scientifically impossible.

Scientists focus on recently extinct species such as the woolly mammoth, the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger), and the passenger pigeon. These animals either went extinct recently enough for some DNA to survive or have living close relatives that can serve as genetic templates. If we ever see extinct animals walking among us again, they are more likely to be shaggy mammoths or elusive marsupials rather than ancient reptiles. Choosing the right candidate is a balancing act between scientific feasibility and ecological responsibility.

Ethical Questions Loom Large Over De-Extinction

Even if we could bring back extinct animals, the question remains — should we? De-extinction raises complex ethical issues that scientists, conservationists, and the public are still grappling with. Some argue that resurrecting species could restore lost ecosystems, boost biodiversity, and correct human-caused extinctions. Others warn that it could distract from urgent conservation efforts for endangered species still fighting for survival today.

There are also concerns about the welfare of the animals themselves. Would a lab-created mammoth be able to thrive in today’s world? Would it suffer from health problems, loneliness, or environmental stresses it is not adapted to handle? Experts urge caution, emphasizing that just because something is scientifically possible does not always mean it is morally right. The idea of bringing back extinct animals taps into powerful hopes and fears about our relationship with nature — and the consequences of playing with life.

Revived Animals Would Not Be Exactly Like the Originals

Even if we successfully recreate an extinct animal, it would not be a perfect copy of what once roamed the Earth. Scientists explain that revived animals would carry genetic differences from their living relatives used to fill in missing DNA. Their environments would also be drastically different from those their ancestors knew. Climate, vegetation, predators, and human activity have all changed dramatically since many of these species went extinct.

This means that de-extinct creatures would likely be hybrids, blending traits from both ancient and modern species. Their behavior, appearance, and survival skills might not match what history or fossil records suggest. In a way, they would be brand-new animals — cousins of the originals, not true replicas. This challenges the romantic idea of “restoring the past” and pushes us to think about how we would treat these new beings if they ever did step back into our modern world.

Habitat Loss Could Doom Revived Species Again

One of the biggest hurdles in bringing back extinct animals is not the science — it is finding a place for them to live. Many of the ecosystems that once supported species like the woolly mammoth or the passenger pigeon no longer exist in their original form. Forests have been cut down, grasslands have been paved over, and climate change has reshaped environments around the globe.

Scientists and conservationists emphasize that without the right habitat, any attempt at de-extinction could be short-lived. Revived animals could struggle to find food, avoid predators, or adapt to landscapes filled with human activity. If their original homes are gone, simply recreating the species would not be enough. It would require rebuilding or preserving ecosystems, a challenge that is massive in its own right. This reality forces us to ask a tough question: are we prepared to create not just the animal but the world it needs to survive?

Some Scientists Want to Use De-Extinction to Boost Ecosystems

Not every de-extinction project is about nostalgia. Some researchers believe that reviving certain extinct animals could actually help restore damaged ecosystems. For example, reintroducing mammoth-like creatures to the Arctic tundra could, in theory, help maintain grasslands and slow permafrost melt, contributing to climate change mitigation.

Ecologists studying this idea argue that carefully selected de-extinct species could play vital roles in rebuilding lost ecological functions. It is a hopeful vision where de-extinction is not just about bringing back lost animals but healing wounded landscapes. However, it comes with big risks. Introducing a new or partially recreated species could have unintended consequences, upsetting delicate ecological balances. The stakes are high, and every step would have to be carefully researched and tested. Still, the idea offers an inspiring glimpse into how science might be used to not only look backward but also repair the future.

Funding for De-Extinction Is Growing and Controversial

Private companies, philanthropists, and even government agencies are starting to invest real money into de-extinction research. High-profile biotech firms are pouring millions into projects aimed at reviving animals like the woolly mammoth, promising breakthroughs not just in conservation but in genetics and medicine too.

Supporters see this investment as a bold leap forward, a way to push scientific frontiers and tackle major environmental challenges. Critics worry it diverts resources from protecting endangered species that still have a fighting chance. Many conservationists argue that funding would be better spent on preventing more extinctions rather than bringing back species that have already disappeared. The growing financial interest in de-extinction shows that the idea is moving quickly from academic debate to real-world action — and that the decisions we make now could shape the natural world for generations to come.

De-Extinction Might Not Undo Human Mistakes

There is a powerful emotional pull behind the idea of de-extinction. After all, many species went extinct because of human activity, hunting, habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. Bringing them back feels like a way to make amends, a chance to set things right. But experts caution that resurrecting a few animals would not erase the damage that caused their disappearance in the first place.

Bringing back an animal without addressing the larger issues that led to its extinction could simply repeat the same tragedy. Without deep systemic changes in how we treat nature, revived species might quickly find themselves endangered once again. De-extinction is a tool, not a solution, and it cannot substitute for the hard work of protecting the ecosystems and species we still have. It serves as a reminder that while science can do amazing things, true restoration of the planet requires a much broader commitment.

Genetic Editing Is Creating “New” Animals, Too

Even when scientists cannot perfectly recreate an extinct species, they can use genetic editing tools like CRISPR to create animals that carry some of the same traits. For instance, researchers are working on engineering modern elephants with mammoth-like characteristics, such as thick fur and cold tolerance, to survive in Arctic environments.

This approach blends conservation biology with cutting-edge technology, creating animals that are not true replicas but new species inspired by extinct ones. Experts suggest that this method might be more realistic than pure de-extinction because it focuses on introducing helpful traits rather than perfect copies. However, it also raises philosophical questions about authenticity, nature, and what it means to “revive” a species. Are we honoring the past, or are we creating something entirely new? The line between conservation and invention is becoming blurrier, and society will have to decide how comfortable it is with walking that line.

The Dream of De-Extinction Is Both Hopeful and Cautionary

At its core, the idea of bringing back extinct animals captures something deeply emotional. It speaks to our guilt over environmental destruction, our wonder at the power of science, and our longing to reconnect with a wilder, more mysterious world. De-extinction offers hope that maybe some losses are not final, that maybe we can undo the mistakes of the past.

But it also serves as a cautionary tale. Just because we can do something does not mean we should rush ahead without thinking about the consequences. Reviving extinct animals is not a magic fix. It is a complex, delicate endeavor filled with scientific challenges and ethical dilemmas. Whether de-extinction becomes a marvel of human ingenuity or a reminder of our hubris depends entirely on how wisely we proceed. Either way, it is a thrilling and sobering glimpse into the future of life on Earth.